My Five Achievements

- A comprehensive library for reduced order modeling in Julia

- Cutting-edge advancements in reduced basis methods for problems defined on parameterized domains

- The successful integration of tensor-train decompositions with reduced basis methods

- Cutting-edge advancements in reduced order models for space-time problems

- A topology optimization library for generating compliant mechanisms in Matlab

A comprehensive library for reduced order modeling in Julia

I am the author of GridapROM.jl, a Julia-based library for the numerical approximation of parameterized partial differential equations using a broad range of reduced order modeling techniques. The library is designed to be both extensible and user-friendly, featuring a high-level, expressive API that promotes rapid prototyping without sacrificing performance. Thanks to Julia's just-in-time (JIT) compilation and advanced lazy evaluation strategies, GridapROMs delivers high efficiency while remaining fully written in Julia. The framework is PDE-agnostic and supports a wide spectrum of applications, including linear and nonlinear problems, single- and multi-field systems, and both steady-state and time-dependent formulations.

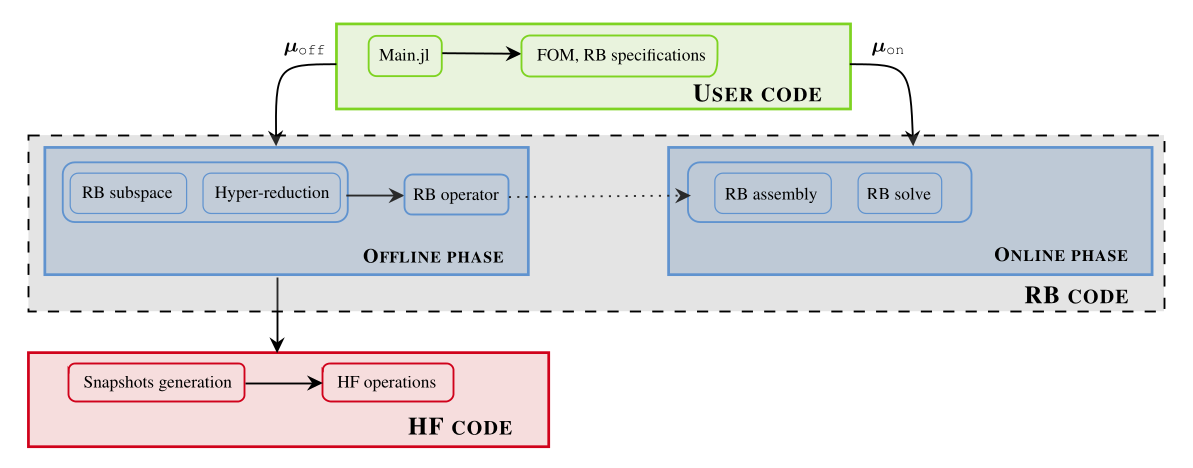

Figure 1: A schematic view of the implementation of GridapROMs.

Figure 1: A schematic view of the implementation of GridapROMs.One of the key innovations of the library lies in the efficient generation of high-fidelity snapshots for parameterized partial differential equations. This is achieved through the lazy evaluation of cell-wise quantities defined over the finite element mesh, significantly reducing computational overhead during data assembly. In parallel, the integration of message-passing interfaces (MPI) enables scalable snapshot generation even for extremely large datasets – potentially comprising billions of entries in time-dependent problems – at fine spatial and temporal resolutions. As a result, the library effectively addresses one of the major computational bottlenecks in reduced order modeling: the cost of generating high-fidelity training data.

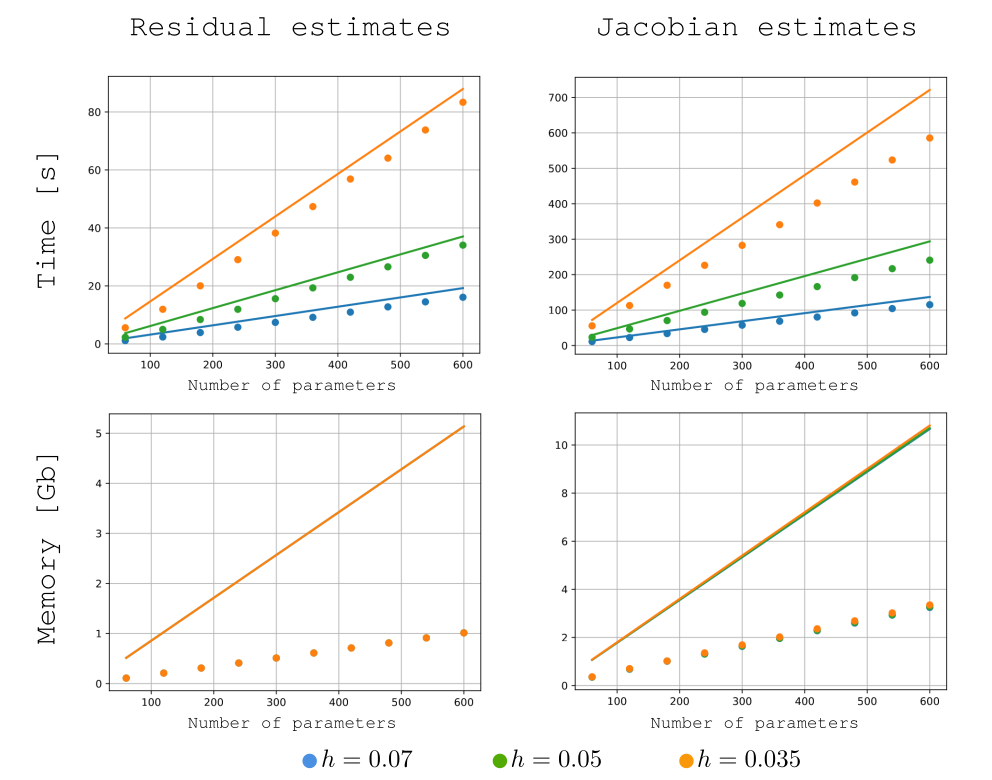

Figure 2: Wall time and memory usage for residual and Jacobian assembly in GridapROMs.jl evaluated on a steady, parameterized Navier–Stokes problem in a 3D geometry, across different mesh resolutions. These measurements are benchmarked against a baseline estimate (solid lines), defined as the cost of assembling a single residual or Jacobian, scaled by the number of parameter instances. The results demonstrate that GridapROMs.jl significantly reduces both wall time and, even more notably, memory usage – highlighting the library's efficiency in handling large-scale parameterized problems.

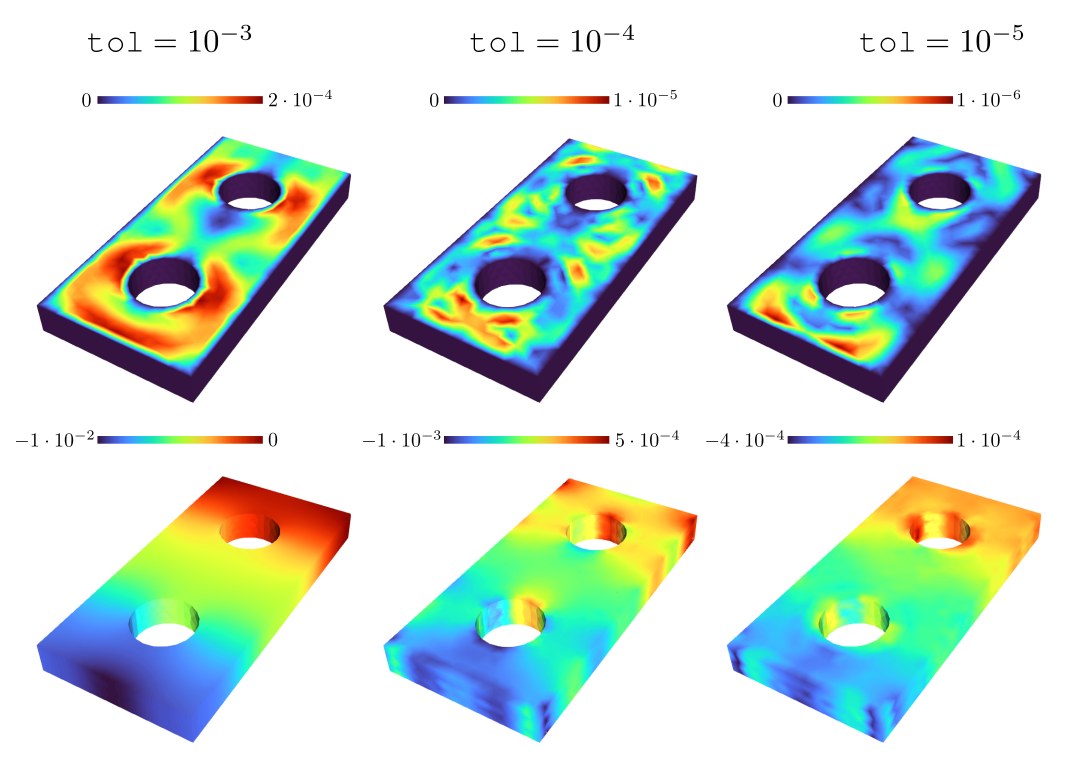

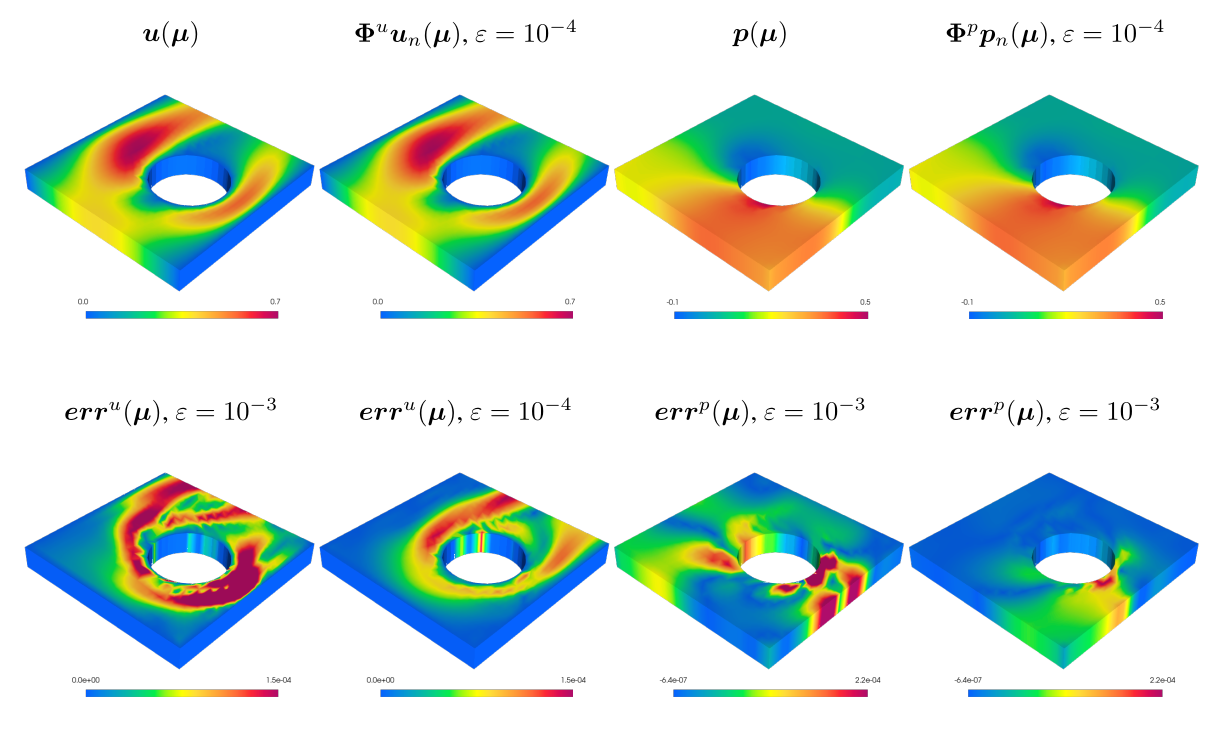

Figure 2: Wall time and memory usage for residual and Jacobian assembly in GridapROMs.jl evaluated on a steady, parameterized Navier–Stokes problem in a 3D geometry, across different mesh resolutions. These measurements are benchmarked against a baseline estimate (solid lines), defined as the cost of assembling a single residual or Jacobian, scaled by the number of parameter instances. The results demonstrate that GridapROMs.jl significantly reduces both wall time and, even more notably, memory usage – highlighting the library's efficiency in handling large-scale parameterized problems. Figure 3: Pointwise error between the finite element solution and the corresponding reduced-order approximations computed with GridapROMs.jl, for a fixed parameter and time instance in an unsteady, parameterized Navier–Stokes problem. The top row displays the velocity magnitude error for varying accuracy tolerances , while the bottom row shows the corresponding pressure field error. These results illustrate the effect of the tolerance parameter on the accuracy of the reduced-order solution.

Figure 3: Pointwise error between the finite element solution and the corresponding reduced-order approximations computed with GridapROMs.jl, for a fixed parameter and time instance in an unsteady, parameterized Navier–Stokes problem. The top row displays the velocity magnitude error for varying accuracy tolerances , while the bottom row shows the corresponding pressure field error. These results illustrate the effect of the tolerance parameter on the accuracy of the reduced-order solution.Cutting-edge advancements in reduced basis methods for problems defined on parameterized domains

Parameterized domains make solving partial differential equations (PDEs) especially challenging: geometric variations complicate traditional reduced-order models, remeshing is often required for each new configuration, and advanced tensor-based methods struggle on non-Cartesian grids. To tackle these issues, I designed a unified framework that combines unfitted finite element methods – where geometries are embedded in a background Cartesian mesh – with deformation-based mappings that transport a reference configuration to any parametrized domain. This innovation ensures that all solution data remain in a fixed-dimensional space, enabling the effective use of both classical and tensor-based reduced basis techniques.

I further enhanced the framework with a localization strategy that builds dictionaries of reduced subspaces and compressed operators, significantly boosting both accuracy and efficiency. I extended the methodology to complex saddle-point problems, including the Stokes and Navier-Stokes equations, through a tailored stabilization procedure. Extensive numerical experiments on benchmark fluid dynamics problems confirm that the approach delivers high accuracy and dramatic computational savings, even for complex parametrized geometries.

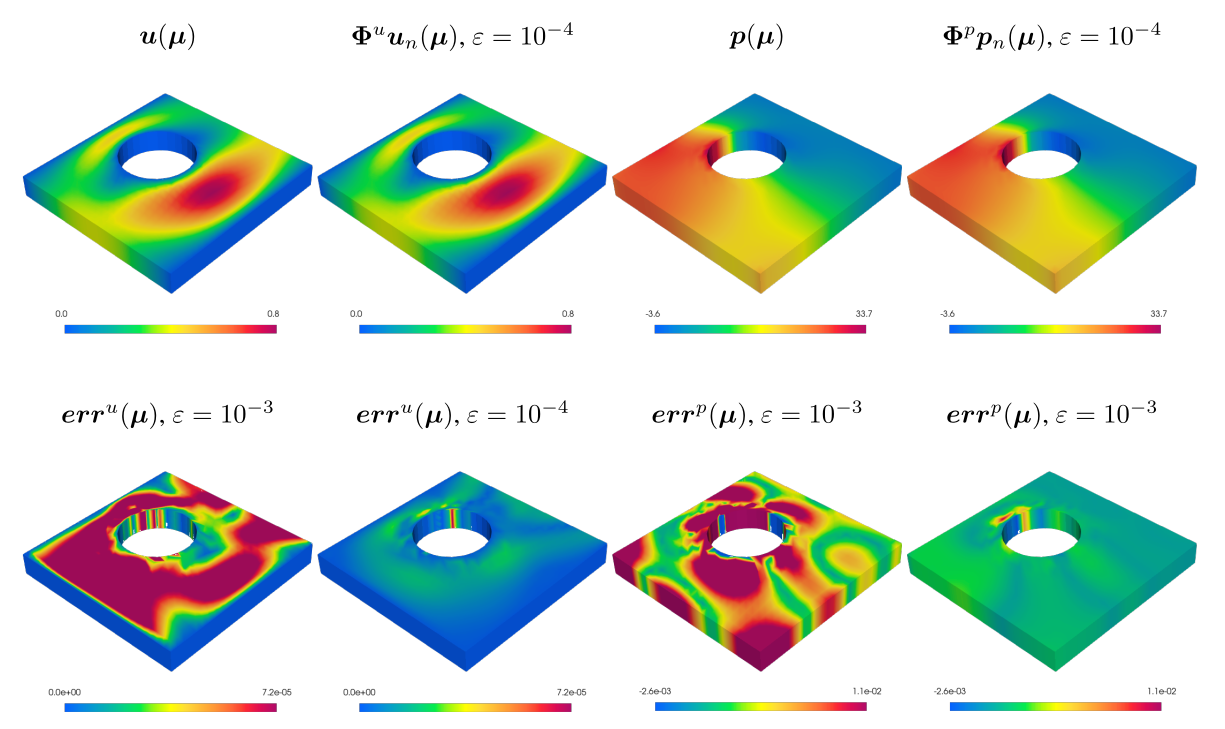

Figure 4: Results for the Stokes equation, on a 3D rectangular geometry with a moving cylindrical hole. Top row: finite element velocity magnitude (left), reduced basis velocity magnitude (centre-left), finite element pressure (centre-right), and reduced basis pressure (right); the reduced basis velocity and pressure are obtained with an error tolerance . Bottom row: point-wise velocity error magnitude (left, with a tolerance , and centre-left, with a tolerance ), and point-wise pressure error (centre-right, with a tolerance , and right, with a tolerance ). Value of the test parameter: .

Figure 4: Results for the Stokes equation, on a 3D rectangular geometry with a moving cylindrical hole. Top row: finite element velocity magnitude (left), reduced basis velocity magnitude (centre-left), finite element pressure (centre-right), and reduced basis pressure (right); the reduced basis velocity and pressure are obtained with an error tolerance . Bottom row: point-wise velocity error magnitude (left, with a tolerance , and centre-left, with a tolerance ), and point-wise pressure error (centre-right, with a tolerance , and right, with a tolerance ). Value of the test parameter: . Figure 5: Results for the Navier-Stokes equation benchmark, on a 3D rectangular geometry with a moving cylindrical hole. Top row: finite element velocity magnitude (left), reduced basis velocity magnitude (centre-left), finite element pressure (centre-right), and reduced basis pressure (right); the reduced basis velocity and pressure are obtained with an error tolerance . Bottom row: point-wise velocity error magnitude (left, with a tolerance , and centre-left, with a tolerance ), and point-wise pressure error (centre-right, with a tolerance , and right, with a tolerance ). Value of the test parameter: .

Figure 5: Results for the Navier-Stokes equation benchmark, on a 3D rectangular geometry with a moving cylindrical hole. Top row: finite element velocity magnitude (left), reduced basis velocity magnitude (centre-left), finite element pressure (centre-right), and reduced basis pressure (right); the reduced basis velocity and pressure are obtained with an error tolerance . Bottom row: point-wise velocity error magnitude (left, with a tolerance , and centre-left, with a tolerance ), and point-wise pressure error (centre-right, with a tolerance , and right, with a tolerance ). Value of the test parameter: .The successful integration of tensor-train decompositions with reduced basis methods

I developed a novel reduced basis solver for efficiently solving parameterized partial differential equations by leveraging the tensor-train format to compactly represent high-dimensional finite element data. This approach yields several key benefits: a substantially more efficient construction of reduced subspaces, a cost-effective hyper-reduction technique for assembling full-order residuals and Jacobians, and a lower-dimensional projection space for a given target accuracy. The method is robust and exhibits convergence rates comparable to those of classical reduced basis methods. It has recently been integrated into GridapROM.jl.

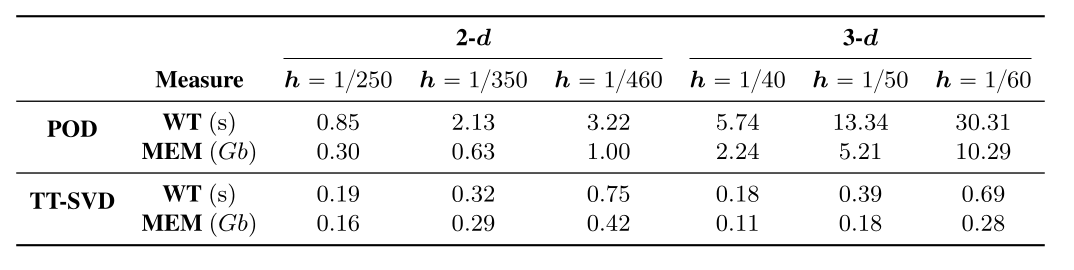

Figure 6: From top to bottom: wall time (WT) and memory allocations (MEM) for constructing an -orthogonal basis using both truncated POD and the tensor-train SVD, applied to a Poisson equation. From left to right: results are shown for 2D and 3D geometries across varying mesh sizes , with a fixed accuracy tolerance of . The results highlight the superior computational efficiency of the tensor-train approach in both runtime and memory usage, compared to the traditional POD-based method.

Figure 6: From top to bottom: wall time (WT) and memory allocations (MEM) for constructing an -orthogonal basis using both truncated POD and the tensor-train SVD, applied to a Poisson equation. From left to right: results are shown for 2D and 3D geometries across varying mesh sizes , with a fixed accuracy tolerance of . The results highlight the superior computational efficiency of the tensor-train approach in both runtime and memory usage, compared to the traditional POD-based method.Cutting-edge advancements in reduced order models for space-time problems

I contributed to the development of advanced reduced order models for the solution of parameterized, unsteady partial differential equations. The main contributions include:

The proposal of a novel discrete interpolation method for the joint space-time approximation of finite element residuals and Jacobians.

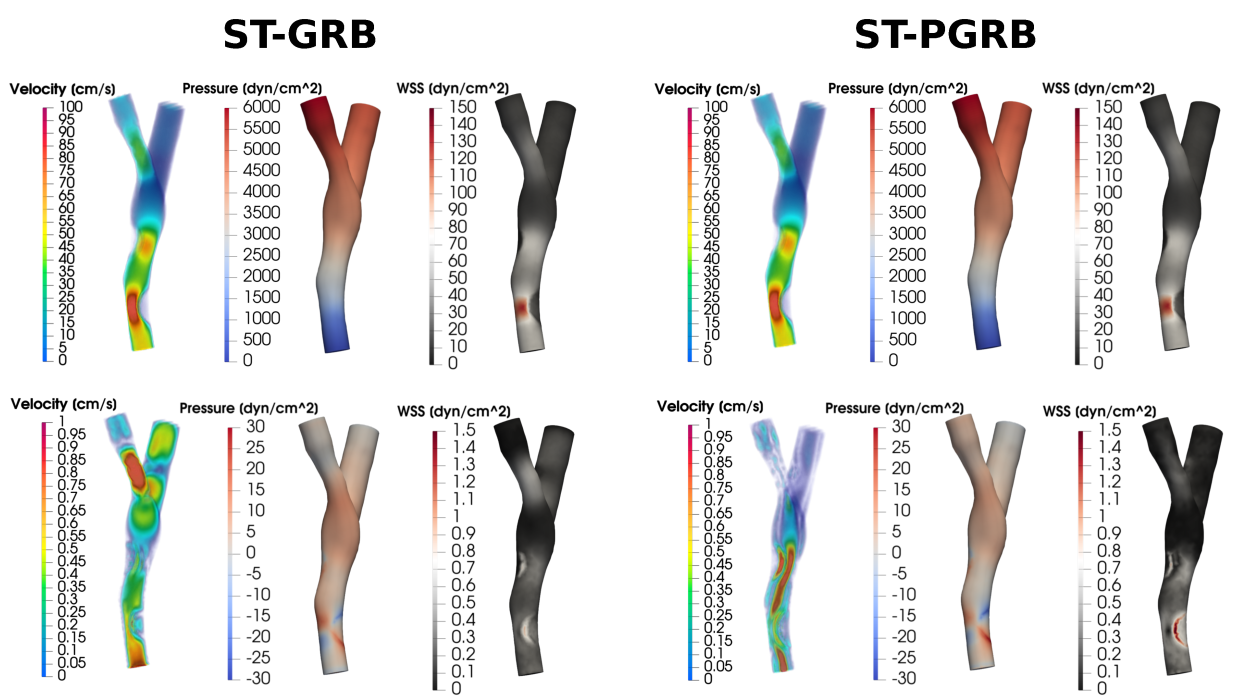

The development of stabilized reduced basis methods for the efficient solution of hemodynamics problems in arterial blocks. These methods significantly enhance the efficiency of traditional spatial-only reduced basis schemes, while maintaining comparable accuracy.

Figure 7: Pointwise error between the finite element solution at a fixed parameter and time for an unsteady, parameterized Stokes equation solved in a Femoropopliteal Bypass, and the corresponding reduced-order solutions computed using a space-time Galerkin reduced basis method (left) and a space-time Petrov-Galerkin reduced basis method (right), across various accuracy tolerances. The first row reports the velocity magnitude errors for tolerances , while the second row displays the corresponding pressure field errors.

Figure 7: Pointwise error between the finite element solution at a fixed parameter and time for an unsteady, parameterized Stokes equation solved in a Femoropopliteal Bypass, and the corresponding reduced-order solutions computed using a space-time Galerkin reduced basis method (left) and a space-time Petrov-Galerkin reduced basis method (right), across various accuracy tolerances. The first row reports the velocity magnitude errors for tolerances , while the second row displays the corresponding pressure field errors.A topology optimization library for generating compliant mechanisms in Matlab

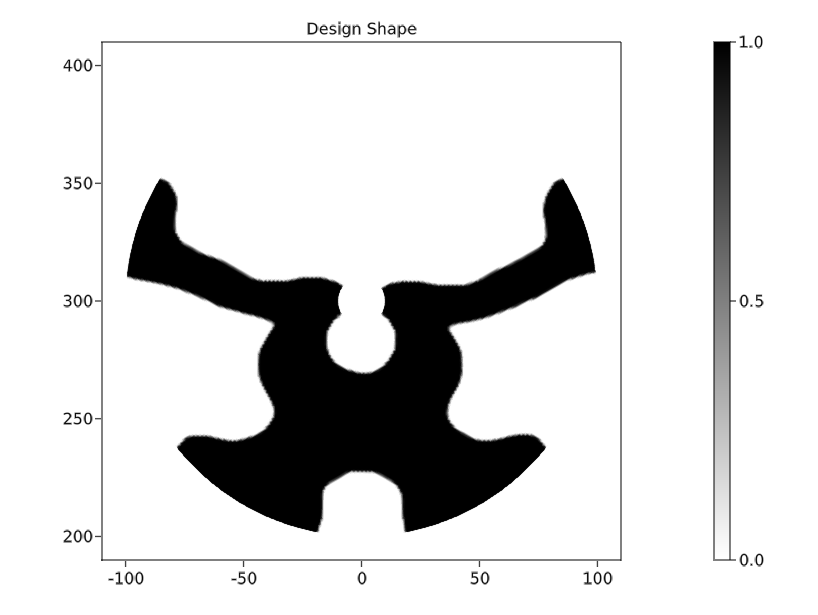

As part of a 6-month internship at CSEM, I developed a topology optimization code in Matlab for designing novel compliant mechanisms tailored to aerospace applications. The generated designs were required to simultaneously satisfy multiple compliance constraints and pass manufacturing-level stress tests, which were carried out using Comsol Multiphysics.

Figure 8: A compliant mechanism generated with a topology optimization solver.

Figure 8: A compliant mechanism generated with a topology optimization solver.